The movie, Big Miracle, and what I witnessed in real life, part 8: Michio Hoshino froze his fingers; I threw away my chance for wealth and fame; Kool-Aid pressure ridge bombs; polar bear; interspecies Pied Piper; tarps over the hole; CNN learns the home is a sacred place

Friday, February 17, 2012 at 1:03AM

Friday, February 17, 2012 at 1:03AM This is reknowned wildlife photographer, Michio Hoshino, outside the North Slope Borough Search and Rescue hangar waiting for a helicopter ride. He has blisters on his fingers because they got frostbit while he was out photographing the trapped gray whales. Michio was born in Japan but loved open space and wildlife, and so relocated to Alaska in the 1970's. In 1996, on Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula, he was mauled to death by a brown bear that attacked him in his sleep and dragged him out of his tent.

This week, a play about him is being performed in Anchorage. If I were not overloaded with tasks between now and when I leave for Arizona/India in two nights, I would go see it.

Except to try to sleep, I did not spend much time at the NARL quonset hut that then served as my Barrow home, but when I was there my phone rang almost non-stop. The calls came from people all over the world who had seen my wire service photos in the planet's newspapers.

One of the first calls came from Newsweek at 6:30 in the morning, after a night in which I had gotten no sleep at all. Newsweek wanted to contract with me on the spot, to commit me to photographing the rest of the rescue for them, in color. Newsweek was prepared to put a few hundred rolls on a jet and send them to me immediately.

My first commitment was to Uiñiq magazine, which then was all black and white and I intended to photograph in black and white. I turned them down.

This was followed almost immediately by a call by lady from SIPA Press out of Paris. She wanted me to swear off any further relationships with the wire services and to commit to shoot exclusively for SIPA - again, in color. She gave me a price. I refused it. She nearly doubled it. I refused it again. She doubled the second figure. I refused it again. "Well, how much do you want?" she pushed. "We can work something out. This one's going to be big." She offered to make black and white dupes from the color slides she wanted me to shoot for her and then send them back, "for your little paper."

She promised me fame and and fortune overnight.

I didn't negotiate. I just told her, "no." She called a couple more times. Same answer. One editor in Sweden proved so persistant that for the next week I received a call from her every time I came within earshot of my phone. There was one magazine that I hoped maybe I could get some photos into - Life. Life was the magazine that had first shown me the magic and wonder of photography. At the beginning of my career, I had given myself two magazine goals - to be published in both National Geographic and Life.

I had made it into National Geographic. I had not made it into Life. Life frequently ran black and white essays. Maybe this was my chance. I called the science editor, Jeff Wheelwright, who loves Alaska and has become a friend. He was on extended vacation, and couldn't be reached. Not long after that, I received a call from Lynn Weinstein at Life's picture desk. She had also seen my wire service pictures. She asked if I would shoot for Life.

Color or black and white? I asked. "Color." She answered. I told her about Uiñiq. I told her I had to shoot black and white. Would she maybe reconsider? She said, no, she would find someone to shoot color, but if I could send her some black and white prints by the following Thursday, she would consider them. That was eight or nine days away - surely, this would end well before then and I would have time to make some high-quality black and white prints and send to her.

Ok, I agreed - but no color.

I promised my UPI reporter friend Jeff Berliner that I would make a print or two for him every day. I did not really want to, because one cannot shoot while one is developing film and printing. I did not want to be distracted from shooting. But I figured I could print after midnight and before first light, when there would likely be no action to shoot.

As I was no one's employee but a free agent, some might not understand how I could put Uiñiq ahead of Life, Newsweek, the wealth and fame promised by SIPA and all the other national and international requests that I received, but - Uiñiq was my creation. It was my magazine. Through it, I was shooting this for the people of the Arctic Slope - most especially, for the Iñupiat people. Of course I would put Uiñiq first.

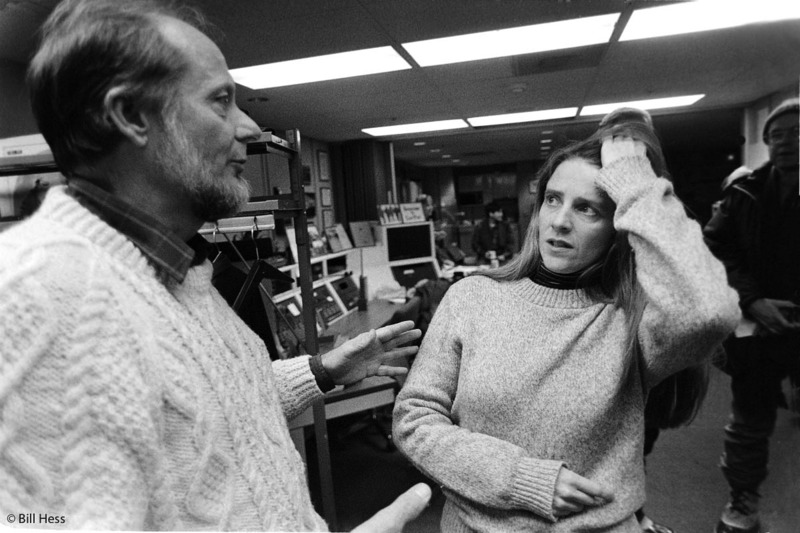

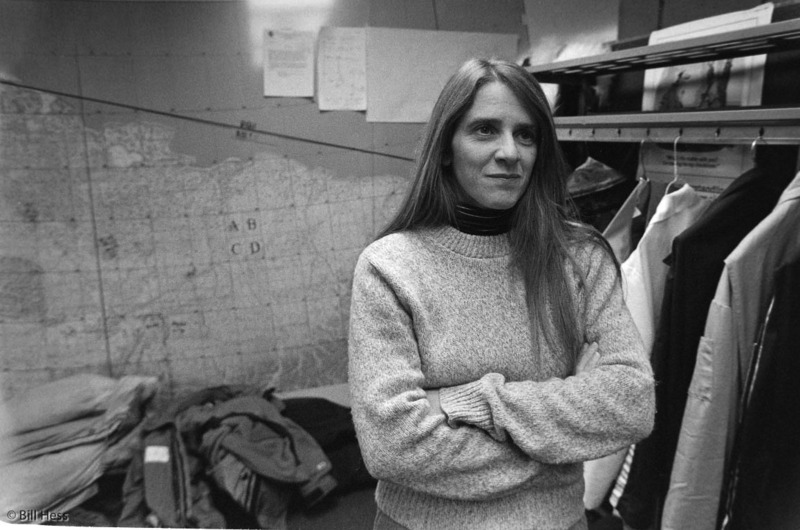

This is Cindy Lowry of Greenpeace, talking to NOAA's Ron Morris, whom the federal government had put in charge of the rescue effort - a charge he took seriously. In the movie, Big Miracle, Drew Barrymore plays Greenpeace volunteer Rachel Kramer, Lowry's fictional counterpart. From all that I read, Lowry is very pleased with the way Barrymore portrayed her.

I would note, though, that there are some major differences between the two. Kramer begins the movie despising the Iñupiat whalers and the hunt that sustains them. When I first learned that Lowry was coming to Barrow, I was prepared not to like her as I thought she might be just as depicted in the movie - someone opposed to the Iñupiat bowhead hunt, someone who wanted to shut it down, someone who could be rigid and unreasonable about the subject.

But she wasn't. When I first met her at the NSB-SAR hangar, she completely disarmed me. She was charming and personable - rational and reasonable. She told me that she had once looked unfavorably at Iñupiat whaling, but had come to understand that it was also a part of the natural order and that she, and Greenpeace, supported the hunt and would continue to as long as it did not threaten the bowhead population.

She was not shrill. She was not extreme. She was passionate. Devoted to her cause. She struck me as a good human being. She found it easy to get along with whalers, to get along with everybody. Well, maybe not quite everybody. She does look a little stressed in this conversation with Ron Morris.

Ron Morris, by the way, had no direct counterpart in Big Miracle - nor did anyone in the NSB Wildlife Management Department, Public Information Office or Mayor's Office. NSB-SAR did have its helicopter counterpart.

At the beginning of the rescue, conversations with Ron were pleasant and amiable, but as the rescue wore on, he grew ever more stressed and conversations with him became ever more stressful.

I guess because I was shooting film and had to conserve in a way I do not have to do now with digital, I only shot two frames of Cindy in this hangar shoot and this is the next - and it immediately followed the frame in which she conversed with Morris.

One day early in the rescue, I stepped into Pepe's (Amigos in Big Miracle) for lunch, found her sharing a table with a man I had not yet seen. Cindy invited me to join them. She introduced me to Jim Nollman, - an "expert on interspecies Communications" from Friday Harbor, Washington. Nollman had his own company - Interspecies Communications and had come to communicate with the trapped whales, lead them to open water and send them on their way to Baja. He had brought tapes of whale sounds, including gray but also orcas, which like to eat grays and of music. He must have also brought a guitar, because he had plans to use one.

If I recall correctly, Greenpeace had paid for his plane ticket in the hope that his gray whale recordings could be used to lead the whales to open water. Yet, after I visited with them for awhile, it became clear that Nollman believed music would be the best lure. He had brought different musical tapes, but what he really wanted to do was to take his guitar out onto the ice, sit at the edge of one of the chainsaw holes that the whales had so far refused to use, strum his guitar and sing to them through a microphone attached to an underwater speaker.

He believed the whales would then leave the security of the breathing hole that had thus far kept them alive and would swim to the one where he sat playing. He would then move a hole away and would strum and sing all over again. In this way, he would lead them all the way to freedom - just like the Pied Piper.

"I need three days and I can lead them to freedom," he told me.

I can't remember for certain if it was at this lunch or another, but I remember that I was eating lunch with Cindy when she first told me that Greenpeace had contacted Soviet officials and were trying to persuade them to send a nearby icebreaker to Barrow, and US officials to get the permission. This was a few days after Ron Morris had first spoke confidentially in the car of Ronald Reagan and how high US and Soviet officials were discussing the possibility of such an icebreaker.

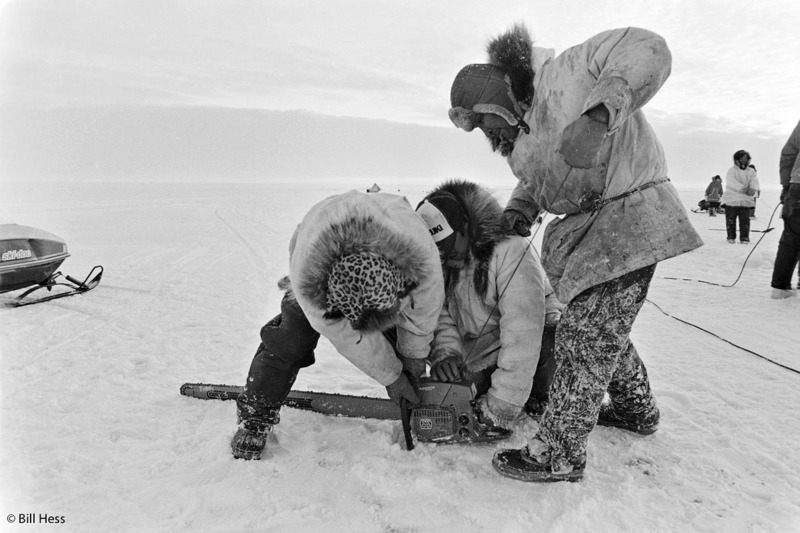

Once the whales did begin to move through the chainsaw holes, it was a fact that their seaward progress would be stopped short by the pressure ridges, if no way was found to clear a way through them. A couple of different possibilities had been discussed - dynamite could be used to blast a way through - this would almost certainly kill and injure other marine life - and might even cause the whales to panic, swim off under the ice and drown.

The other possibility involved sending the Sky Crane and ice punch back out to hammer at the ridge and weaken it so a gap could be cleared through it. The oil industry and the National Guard remained eager not only to help but to prove they could get the job done, so this was chosen over dynamite. Two local Iñupiat ice experts were sent by helicopter out to the pressure ridges to search for structural weaknesses in the ridges - senior whale hunters Whitlam Adams and Alfed Leavitt.

They would seek out structural weaknesses. NSB senior scientist Tom Albert would then mark those spots with red cherry Kool-Aid bombs.

Alfred Leavitt. When he was a young man, Alfred had once taken his dog team onto the ice to hunt and had taken a polar bear. All by himself, he pulled and tugged and hoisted the bear onto his sled, then began the return trip to Barrow - only to discover the ice he was on had broken off from the shorefast and was drifting seaward. A lead, about 100 feet wide, separated him from safety. He ordered his dogs into the water and they obeyed. As they swam, he rode the sled with the bouyant polar bear, but still went in up to his waist. When he reached the other side, he jumped onto the ice just as the last couple of dogs in the team went under. He shoved his hands into the water and pulled them out.

When he was an old man, he again went hunting on the sea ice, this time by snowmachine instead of dogs. He again got a bear. Again, he strapped it to his sled. Again, he found himself cut off from land by a break in the ice and a growing lead of about the same breadth.

This time, he took as good a run at the water as he could, then went skipping across the lead on his snowmachine. The snowmachine sank just before he reached the other edge. Alfred took out his knife and shoved it into the ice as a grip to hang onot. Another nearby hunter spotted him, came and helped pull him out.

Alfred, by the way, was the father of chainsaw crew boss Johnny Leavitt.

Whitlam signals to Tom in the chopper. Now, I am sad and frustrated. I took some pictures of this scenario that had both Whitlam and the chopper in it and they are much better than this one - in fact, I am certain one of them would have made the dozen or so I plan to put in my store and offer up as prints.

I found the contact sheet. I found a packet of negatives with the same number as the contact sheet - but it had different negatives in it. I opened nearby negative packets - none of them contained it. I found the contact sheet that had the same images as the negatives I found in the packet. They weren't there. At random, I pulled up other negative packets and, in the process of "scanning" images for this series, have opened up almost all the packets.

I cannot find the picture. So I had to substitute this one for it. I am so disappointed. I hope I find it someday.

Here is Tom Albert, dropping a Cherry Kool-Aid bomb from the helicopter at one of the places where Whitlam had signaled. The Sky Crane - ice punch would come back and batter those places, but with little if any effect.

And here is a polar bear as seen from the helicopter. ADN outdoor reporter Craig Medred was in the helicopter with me when I took this picture. He then went back and wrote an article speculating as to the ethics of saving trapped whales, which, left to the natural order of things, could have wound up feeding a bunch of polar bears. What if the polar bears starved because they did not get to eat the whales? The story appeared nationwide.

This caused such an outrage among readers that the Daily News had to pull Medred out of Barrow. They replaced him with their top investigative reporter, Richard Mauer, who then also became the New York Times reporter for the duration.

Polar bears were once hunted in Alaska for sport, but no longer are. Only Natives of the Arctic Coast can hunt them, for "subsistence" purposes. Medred is a skilled and enthusiastic hunter and has taken about every kind of game that can be taken in Alaska, except for polar bears and other sea mammals.

"What a beautiful animal!" he exclaimed as we flew over this one. "I sure would like to shoot one."

Jim and Cindy went to the gray whales while I was out with Alfred and Whitlam and Jim conducted his Pied Piper musical experiment - not with a guitar, but with recorded sounds, piped into the water of one of the newly cut chainsaw holes with his underwater speaker. I missed it.

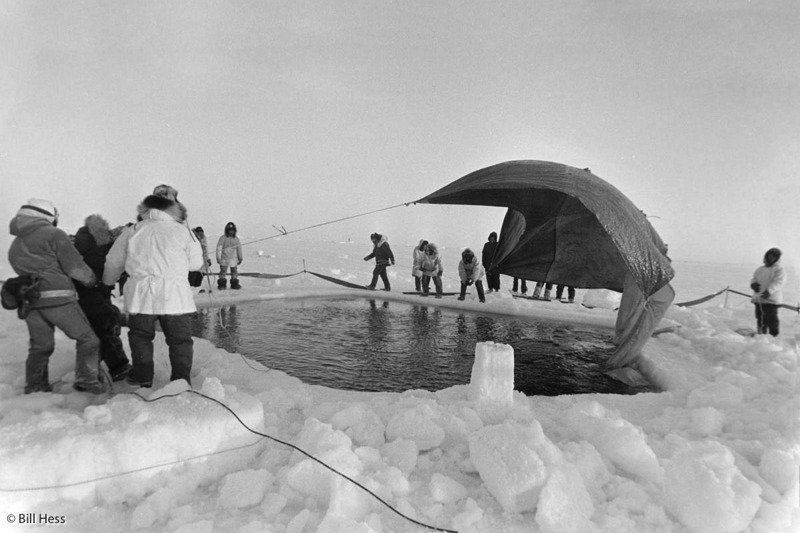

The whales did not budge from the original hole. There had been talk of covering the old hole with ice to force the whales out, or to remove the bubbler and let it freeze over, but this was rejected out of the fear of the damage the whales might suffer if they refused to leave and just kept trying to swim in the refilled hole.

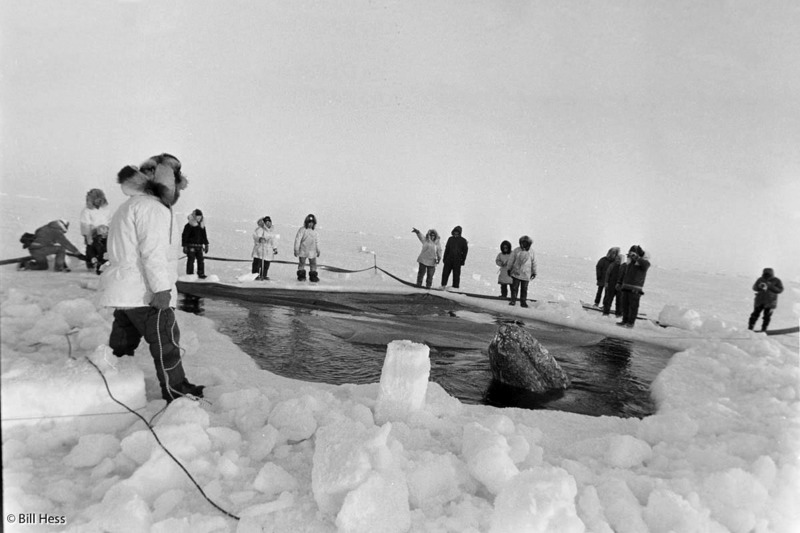

Instead, a decision was made to cover the hole with tarps. Perhaps this would make it so unpleasant for the whales they would leave and go to the chainsaw holes.

Crossbeak beneath the tarps.

The whales not only appeared comfortable beneath the tarps, they seemed to like them. As always, there were those who could not resist the urge to reach out and pat a whale on the snout.

Please note the bubbler - bubblers were also being kept in the newly cut holes to keep them open until the whales decided to use them.

The experiement failed. A whaler pointed toward the open ocean. "Go that way!" he shouted.

Sometime afterward, I was talking to crew boss Johnny Leavitt when we suddenly heard Mark Fraker, an oil industry biologist who got deeply into the rescue, shout. "they're moving!"

We turned. A whale rose in the hole immediately behind us.

A bit later, someone observed that the small whale, Bone, was missing. Someone else then said that he didn't think he had seen Bone since Nollman had conducted his experiment. I thought he might be making a joke, but I was told that a TV reporter also heard the comment and broadcast it as fact.

I talked to Nollman later and he was vehement that this was not the case. He said all three whales were there when he left. He believed his experiment had convinced all the whales to use the chainsaw holes.

Bone was never seen again.

At 2:30 AM the next morning I preparing to develop and print when the CNN reporter and a cameraman burst into my office and demanded Geoff Carroll's phone number. He wanted Geoff to confirm that Bone was dead. I figured Geoff needed his sleep and so conveniently forgot his number. The reporter then ordered me to take him to Geoff's house. He knew he lived in one of the nearby quonset huts. I told him I wouldn't do that. "Then I will go knock on every door over there until I find him," he threatened.

At 2:30 AM the next morning I preparing to develop and print when the CNN reporter and a cameraman burst into my office and demanded Geoff Carroll's phone number. He wanted Geoff to confirm that Bone was dead. I figured Geoff needed his sleep and so conveniently forgot his number. The reporter then ordered me to take him to Geoff's house. He knew he lived in one of the nearby quonset huts. I told him I wouldn't do that. "Then I will go knock on every door over there until I find him," he threatened.

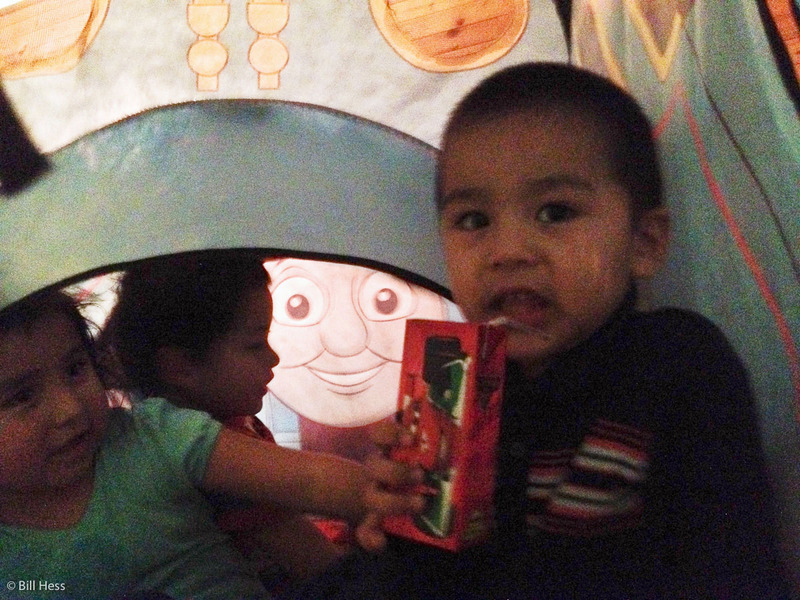

He meant it. I reluctantly agreed. He wanted to ride in his truck, but I walked and made him and his cameraman walk, too. Geoff was not pleased to be woken up, but for all his physical and mental toughness, he is a gentle, mild-mannered person and did not protest too strongly. The reporter grilled him about Bone - was Bone dead? Geoff noted that Bone had not been seen and so had undoubtedly perished. Next, the reporter wanted to do a live interview over the phone, right then.

"Well, okay, I guess," Geoff responded. Marie then came out from the bedroom. She scolded the reporter for being "very rude," pointing out they had been getting hardly any sleep and had a new baby to care for. "There will be a press conference in the morning," she said. The reporter was already setting up the phone interview. He called Geoff to come over.

"No," Marie stopped him. "There isn't going to be a phone interview. I am the Borough Public Information Officer, my husband is a Borough employee and even though he is my husband, I can order him not to talk about this until the press conference tomorrow morning. In fact, that's what I'm doing. I'm ordering him not to talk to you about it."

The reporter did not give up, but presented this argument and that, about how the world needed to know, right now. "No! The home is a sacred place. We are not to be disturbed like this in the middle of the night again!" The reporter tried to argue further, to no avail.

I had taken the picture above just days before: Geoff, Marie, baby Quinn and some mostly young members of Geoff's dog team outside the quonset hut - their home, a sacred place. The dog house is sacred, too - but not the one the CNN reporter found himself in.

p>

Complete series index:

Part 2: Roy finds the whales; Malik

Part 5: To rescue or euthanize

Part 6: Governor Cowper, ice punch, chainsaw holes

Part 7: Malik provides caribou for dinner

Part 8: CNN learns home is sacred place

Part 9: World's largest jet; Screw Tractor

Part 11: Portrait: Billy Adams and Malik

Part 12: Onboard Soviet icebreakers