The following summer, a number of gray whale carcasses lay on the beaches north and south of Barrow. About twenty miles to the southwest, Malik found two together and believed these might be Crossbeak and Bonnet. He reported his find, then returned to the site with NSB Wildlife biologists Craig George and Geoff Carroll, Marie Carroll and the Carroll's one-year old son, Quinn. I came along. One carcass lay on the beach, completely out of the water. The tail of the second lay on the beach, its body extended at an angle outward into the water. The biologists took measurements and studied the condition of the whales. The one lying on the beach measured twenty-six feet in length, seven inches off of the in-water length estimate they had made for Bonnet. Malik knelt at its head. A fond smile crossed his face as he gave the dead whale a pat.

After comparing the skin damage and noting the distance the carcass had been pushed up the beach, the biologists concluded this was not Bonnet, but rather a whale that had likely died the year before the rescue. The other dead whale measured more than forty feet, compared to the thirty-foot estimate the biologists had made for Crossbeak. Here Craig George measures the bigger whale.

Many whale watchers venture each winter to Mexico's Sea of Cortez to observe gray whales. Following the rescue, the call went out for people to look for Crossbeak and Bonnet. The wounds they had suffered in Barrow would have turned to scars that should have been easily identifiable to those who knew what to look for. No sightings were ever reported.

Some people have told me that the observations in the Sea of Cortez are thorough enough that if the whales had shown up there, they would likely have been spotted and identified.

Still, the ocean is a big place and as big as whale is, by comparison it is a small thing. So, when it comes to the two gray whales, people are free to believe whatever they want: the whales swam free and lived; the whales died, if not at Barrow, somewhere enroute.

Whatever happened, it does not seem that there will ever be any way to verify it.

At the moment, I have no further funding to continue Uiñiq. It feels to me like my days making that magazine are over. So far, the magazine has had three incarnations, so I can't say for certain. I have thought this before and then, sooner or later, I have been asked to do an issue, or a few issues. Maybe at some, someone with the authority to fund it will want me to make Uiñiq again and if that should happen, I think it almost a certainty that I would - provided that the opportunity came with the necessary amount of freedom.

Uiñiq is one of the great loves of my life - not because of the paper and ink that it is made of, but because it has given me the opportunity to become somewhat familiar with a climatically harsh but fantastic piece of the globe, and to walk and boat and snowmachine among rugged, smart, and good people who have allowed me to document their way of life and who I have been fortunate to have been befriended and even adopted by.

The first incarnation began at the end of 1985 and lasted through the third quarter of 1996, when circumstance forced me to walk away from Uiñiq, and not without tears.

My love and ties to Barrow and all the villages of the Arctic Slope remained strong and the following summer, 1997, with a little help from the school district, I found my way back for a short visit. During that visit, Roy Ahmoagak invited me to go on an ugruk (bearded seal) hunt with him and his cousin, Richard Glenn.

As we motored through the July icebergs of the Chukchi Sea, a gray whale suddenly lifted its flukes up in front of us...

...

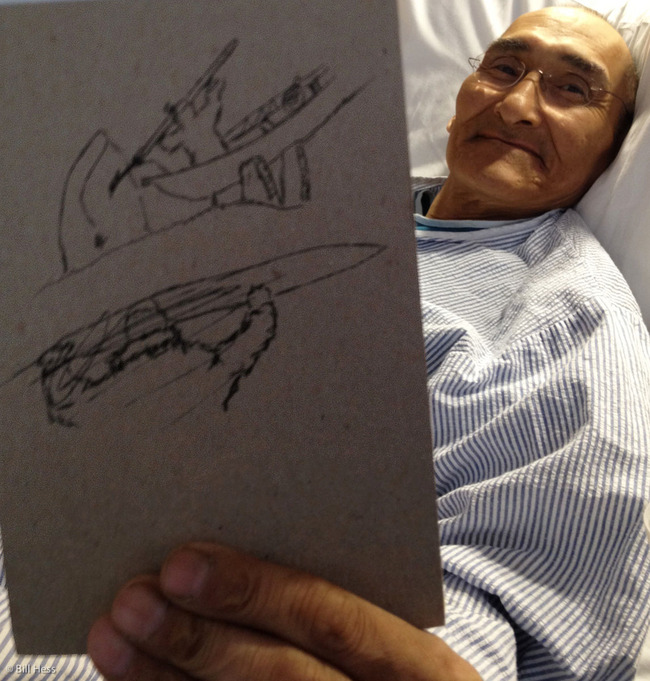

... please note the scars on the tail... many of these were likely made by the teeth of killer whales, perhaps some by the claws and teeth of polar bears, others by sharks - all members of the gantlet that Crossbeak and Bonnet would have had to swim through...

...

In early October of 2002, I received a phone call from Roy Ahmaogak, who spoke in a subdued and hurt voice. He informed me that a bowhead had been taken near Barrow. As always, the hunters attached a line to the whale and several boats hooked up to tow it back to shore. Somehow, the boat that Malik was in got in a tangle and flipped upside down. The others in the boat escaped, but Malik got trapped beneath. Before his fellow whalers, Roy included among them, could right the boat and save him, Malik drowned.

He died as he lived - whale hunting. Shortly afterward, I was contacted by the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation and asked to make a large, framed, print of this photo for display at the funeral. The photo now hangs in the Iñupiat Heritage Center - Barrow's museum. I badly wanted to go to the funeral, but it came at one of those moments of famine in the feast-and-famine cycle that I live through as a freelance photographer. I did not have plane fare. The fact that I missed the funeral is one of my great regrets. Normally, a body will be transported from the funeral site to the graveyard in the bed of a pickup, but little Malik - the Little Big Man, Ralph Ahkivgak, was so beloved by the people of Barrow, whom he had served, taught and helped to feed throughout his life, they spontaneously hoisted his coffin onto their shoulders and carried him to the cemetery, where he was laid to rest in the permafrost.

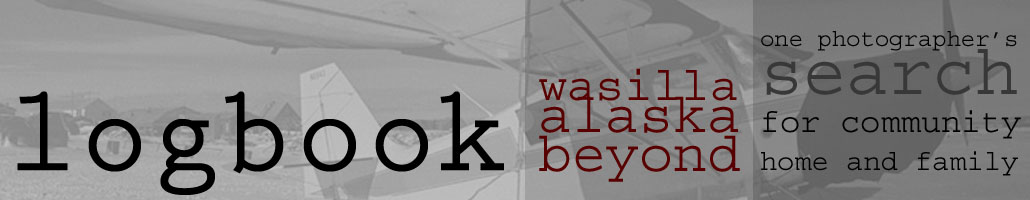

Malik - the man who could watch a whale dive, then direct the crew to a certain spot and that is where the whale would rise. Malik, who befriended three gray whales stuck in the ice off Barrow and became instrumental in the effort to rescue them. Craig George said this about Malik's role in the rescue:

"Malik seemed to have a rapport with the whales. I can tell you one thing I learned. We had gray whale biologists here, all kinds of people, but Malik was the one to listen to.”

"He was looked up to as a man with great knowledge and he taught a lot of young guys," said Roy Ahmaogak. "He meant a lot to Barrow and a lot more to me, because I knew we were in good hands when we were with Malik. We didn't need any gps or technology, because he knew the ocean very well."

One day in the summer after the rescue, I stopped by Malik's tiny house in Browerville for a visit. He told me that when I had seen and heard him talking to the gray whales during the rescue, what I hadn't heard was the gray whales - but he did hear them. Just as he spoke to them, they spoke to him. “‘Malik, we’re scared,’ they tell me. ‘Malik, we’re scared. Help us, Malik. Help us.’ I tell them, ‘Don’t worry. It’s going to be all right. We’ll get you to the lead. You’ll be safe there.’”

And in the eyes of the late, great, whale hunter and whale rescuer, I saw tears.

Complete series index:

Part 1: Context bowhead hunt

Part 2: Roy finds the whales; Malik

Part 3: Scouting trip

Part 4: NBC on the ice

Part 5: To rescue or euthanize

Part 6: Governor Cowper, ice punch, chainsaw holes

Part 7: Malik provides caribou for dinner

Part 8: CNN learns home is sacred place

Part 9: World's largest jet; Screw Tractor

Part 10: Think like a whale

Part 11: Portrait: Billy Adams and Malik

Part 12: Onboard Soviet icebreakers

Part 13: Malik walks with whales, says goodbye

Part 14: Rescue concludes

Part 15: Epilogue

Friday, June 15, 2012 at 8:00AM

Friday, June 15, 2012 at 8:00AM  Alaska Airlines,

Alaska Airlines,  Anchorage,

Anchorage,  Barrow,

Barrow,  Denali,

Denali,  Tom Mahoney,

Tom Mahoney,  stewardess in

stewardess in  Aircraft,

Aircraft,  Alaska,

Alaska,  Logbook entry,

Logbook entry,  Wasilla,

Wasilla,  bicycle

bicycle