The movie, Big Miracle, and what I witnessed in real life, part 2: introducing Malik, Roy Ahmaogak, Price Brower, and the gray whales themselves; first physical contact

Saturday, February 4, 2012 at 9:27PM

Saturday, February 4, 2012 at 9:27PM The movie, Big Miracle, begins with a scene in which Malik and his young grandson Nathan are in an umiak (skin boat) with their crew, paddling toward a bowhead. Later in the movie, Nathan makes a comment to his Aapa Malik that makes it clear that Malik does not use, or believe in using, motor boats to hunt whales.

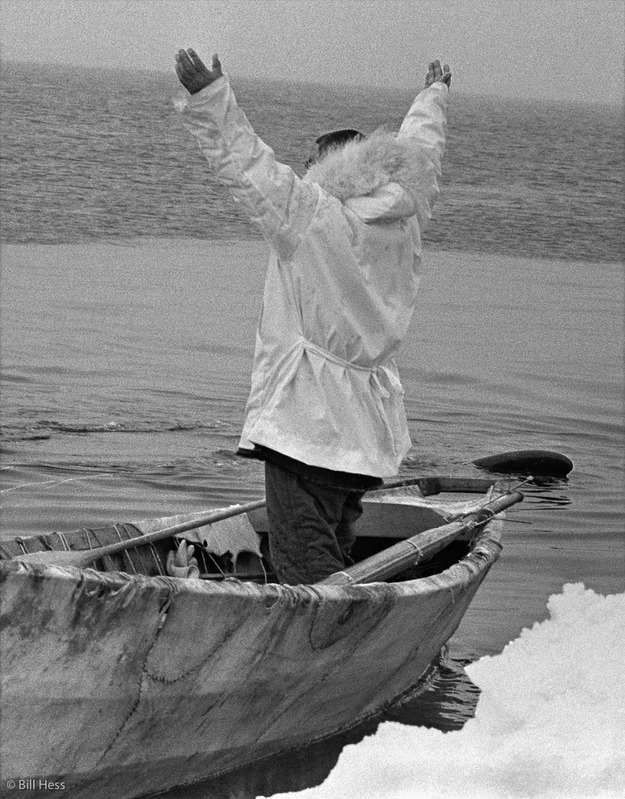

Now I introduce you to the real Malik in a picture that I took about a week before Roy Ahmaogak discovered the three stranded gray whales. That's Malik - standing at the front of the boat, his baseball cap on his head, bill upturned, as it always seemed to be. The fluttering flag is the banner of the Patkotak crew of Barrow, captained by Simeon. With Malik as their harpooner, they have just harvested a bowhead and after a tow of many hours are about to land it at the edge of Barrow.

As you can see, Malik is in a motor boat.

In real life, Malik, as Iñupiat hunters tend to be, was an adaptible and practical person when it came to hunting. In the spring, the Chukchi Sea offshore Barrow is covered by two platforms of ice - the grounded shorefast ice which usually extends four to seven miles offshore - and the polar pack ice, always drifting, floating, swirling around the North Pole.

A lead, sometimes very narrow, sometimes so wide one cannot see acoss it, develops between the shorefast ice and the polar pack. The bowheads that migrate through this lead system to summer feeding grounds in the eastern Beaufort Sea can appear anywhere within the breadth of the lead, but they often travel very close to the edge of the shorefast ice.

Then, the most practical and sensible thing to do is to camp at the edge of that ice, with a quiet umiak, and when a bowhead comes swimming close in, to launch, paddle to the whale, and harpoon it. If it is not an instant kill and the whale swims off, motor boats will be launched to give chase.

The fall hunt is a very different matter. While there may be plenty of ice pans and icebergs floating in the ocean, for the most part it tends to be open. In such conditions, a motor boat is a much more practical and efficient tool than an umiak. So, being practical, efficient, intelligent people, the hunters leave the skin boats behind and go out in motor boats - just as Malik and the Patkotak crew had done on this day.

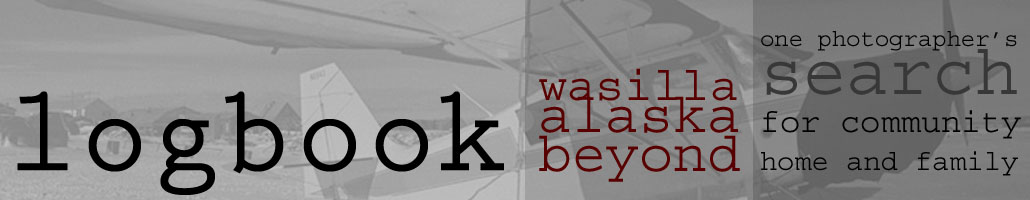

As you can see, quite a bit of ice was floating around in the Chukchi near shore - more than is normal for early October. This early buildup would continue until ice conditions would become just right to trap three young, juvenile gray whales in its clutch.

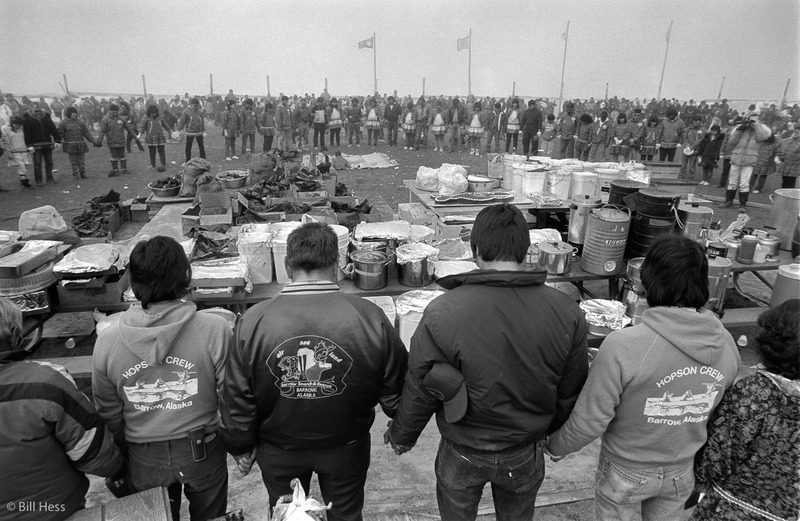

In addition to the Patkotak Crew, the ABC crew, captained by Arnold Brower, Sr., an elder who would also play a crucial role in the gray whale resuce, landed a bowhead that same evening.

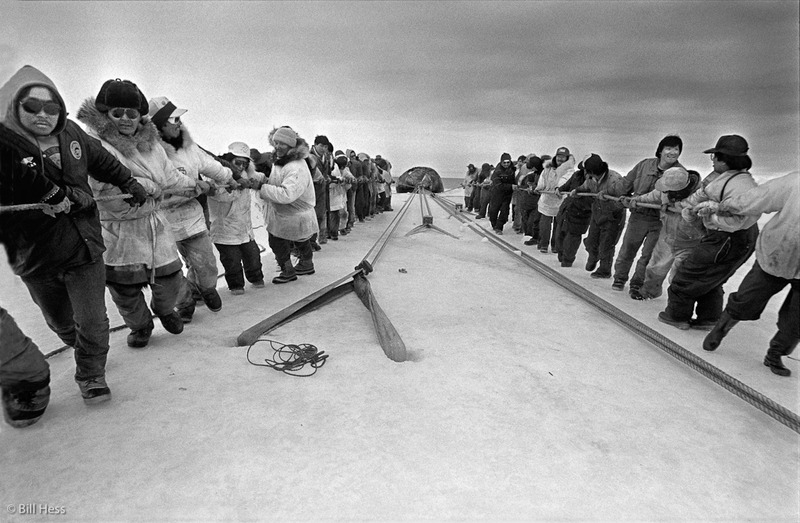

In the spring, the people use manpower to haul the whale out onto the ice, but in the fall, with the whales being brought to land at the edge of the village, it is practical and logical to use big D-9 Cats to pull the whales out of the water, so that is what they do and that is what they did.

Even so, the hard, heavy, work of cutting, dividing, cooking and storing the whale would remain an act of physically demanding, intensive, labor. The work would continue all night long, through the next day and beyond.

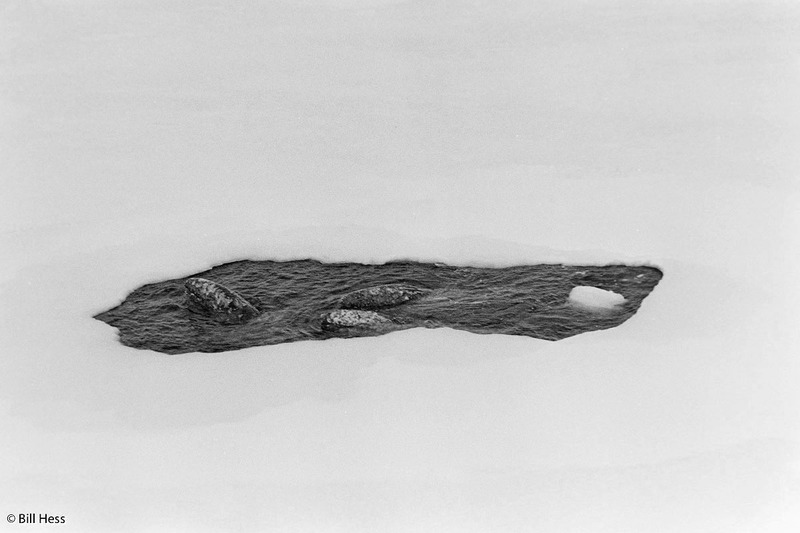

As soon as the Patkotak and Brower whales been taken care of and the community fed, Malik went back out into the Chukchi in a motorized, aluminum boat to harpoon for the Savik crew, captained by Lawrence Ahmaogak - Savik. Savik stayed on land and put his son, Roy, in charge.

Also in the boat were Billy Itta and Roy Okpik.

It was an overcast but calm day. Visibility was good, broken by small patches of fog. After they had been out awhile, Roy and crew heard a report of a nearby bowhead, spotted by hunters in other boats. Malik instructed Roy to head towards those boats. Some crews had tried to go for the whale, but it had dived and eluded them.

"When we got close," Roy recalled afterward, "the whale stayed up. It never tried to go away. It just stayed up, as if it wanted to give itself to us."

Malik stood at the front of the boat. He raised the harpoon over his shoulder as Billy readied himself with the shoulder gun. The whale waited as Roy steered the boat until it was practically on top of the bowhead. Malik, who had been known to jump right onto the back of a whale to harpoon it, thrust his weapon into the whale, sinking the harpoon, attaching the float and firing the bomb-loaded darting gun. Billy then fired the shoulder gun and Okpik tossed the float. The explosions of the bombs reverberated through the boat. Nearby crews helped put another four bombs into the whale and in 15 minutes it was dead - its gift given and received.

A total of 22 boats joined in the tow and it took many hours to drag the bowhead through the water to shore, where the hunters were greeted by many happy people. That's Malik, in the foreground at right, exchanging a hug with Darlene Matumeak Kagak. Behind him is Roy Ahmaogak, holding his young son, Bennie. James Matumeak reaches out to embrace them both.

To their side is Jana Harcharek, an educator who, in 2009, was named Iñupiat of the Year for her leadership in in developing Iñupiaq language curriculum for students of all ages.

When Roy had finished up his part of doing the cutting, storing, putting up the whale and feeding the community, he took a bit of rest. When he awoke, he got the urge to go back down to the ocean to see how conditions looked - perhaps even to spot a whale. Barrow had used up its strike quota but to the east, heavy ice conditions had forced the village of Nuiqsut to stop its hunt without using their three strikes. If conditions stayed good enough here, the odds were good that Nuiqsut's remaining strikes would be transferred to Barrow.

Roy wanted to be ready.

This time, Roy traveled not by boat but by snowmachine. He left his home in the Browerville subdivision of Barrow and traveled on and along the broad sand spit that ends at Point Barrow, about ten miles away.

It was Friday, October 7, 1988. Near Plover Point, just south of Point Barrow, he saw something quite unexpected. There was no open water now, but slush, locked in place between the shore and a high pressure ridge that had formed a few miles out.

Roy was surprised to see three gray whales, surfacing in three holes that they kept open in the slush. If they had been bowheads, the slush would not have bothered them. They would have sliced through it as if it were nothing.

But gray whales do not have the same thick, tough, ice-breaking heads that bowheads do.

Roy returned to Barrow and reported what he had seen to the North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management.

Before much more time passed, Billy Adams, a whaler who worked with NSB Wildlife Management, led me by snowmachine to the shore from where the whales could be seen.

The slush had yet to harden into ice. It could not be walked on. Now, only two holes remained open, one a couple of hundred yards from shore, the other maybe 200 feet.

The holes were empty when Billy first pointed then out to me. Then, a snout rose into one, followed by that hollow, blast of a sound that a whale makes when it exhales.

Soon, another whale followed. Shortly thereafter, another. A bit later, the third - the smallest one, the tip of its snout already eroding from pushing through and scraping against the slushy ice.

After a bit, the whales moved to the other hole, and then they kept going back and forth between the two holes. It was both wonderful and horrible to witness. Wonderful, because it is always wonderful to see a whale, and to hear the hollow, blasts of their breath. Horrible, because in those breaths I heard both their desire and desperation to live - and I did not believe they had much time left to live. Their deaths could potentially be drawn out and miserable, as the slush hardened and the ice slowly enclosed over and suffocated them to death.

The best thing, it seemed to be me, would be for skilled hunters to come and quickly put them out of their misery. Yes, so far, all the hunters that I heard had agreed that these gray whales should be given some time, to see if maybe a hard wind would blow from the west and sweep the distant pressure ridge and this slush out to sea and so free the whales. If that failed, then perhaps the hunters themselves might think of something - I couldn't imagine what, but, again and again, I had been amazed at the incredible resourcefulness the hunters had shown in dealing with all kinds of challenges on their frigid ocean homeland.

Yet, how could they possibly deal with this?

Traditionally, the Iñupiat never hunted grays on a regular basis. A wounded gray whale can be very dangerous. The skin is so riddled with barnacles that the maktak - the skin and the blubber attached to it - does not make good food - but of course, the flesh would be good. Historically, when hunters have found sea mammals, be they seals, walrus, belugas... whatever... stranded in an ice hole, it was like a gift given to them from the creator, something to accept and rejoice over.

Still, in this case, the whalers were ready to wait a bit, give the whales some time, talk it over, see what developed.

How did these whales get into this predicament?

They were all young whales, juveniles with much to learn. No one can be certain, but perhaps they were like teenagers, lollygagging and having a good time doing whatever they pleased while their older and wiser forebearers and their more obediant young peers hurried off on their way to Mexico.

Freeze up came very early. The three gray whales found themselves trapped.

On the shore, just a yard or two from the slush, I found this seagull, frozen in the snow. Billy and I climbed onto our snowmachines and drove back to Barrow.

I think it was two days later when I boarded a North Slope Borough Search and Rescue helicopter along with Dr. Thomas Albert, Senior Scientist of the NSB Wildlife management and some other biologists. Between my first visit and this one, Oran Caudle, a videographer who worked at the North Slope Borough TV Studio, had been helicoptered out to shoot some video from the shore.

I knew that if word of these trapped whales reached the outside world, the major media would flood into Barrow. I had seen the huge amount of interest generated by the exploits of "Humphrey," the humpback whale who had repeatedly swum into the Sacramento River, migrated upstream and then had to be rescued.

I was certain that these whales would generate the same interest - but perhaps even more so, because their situation was so much more dire - impossible, it appeared to me.

I hoped that I could just quietly follow whatever was about to unfold until this saga reached what I was certain would be its tragic end. I did not want to disturbed by outside media. I hoped that Oran would demonstrate the good sense to keep quiet about what he saw and keep the tape close until the event had played itself out.

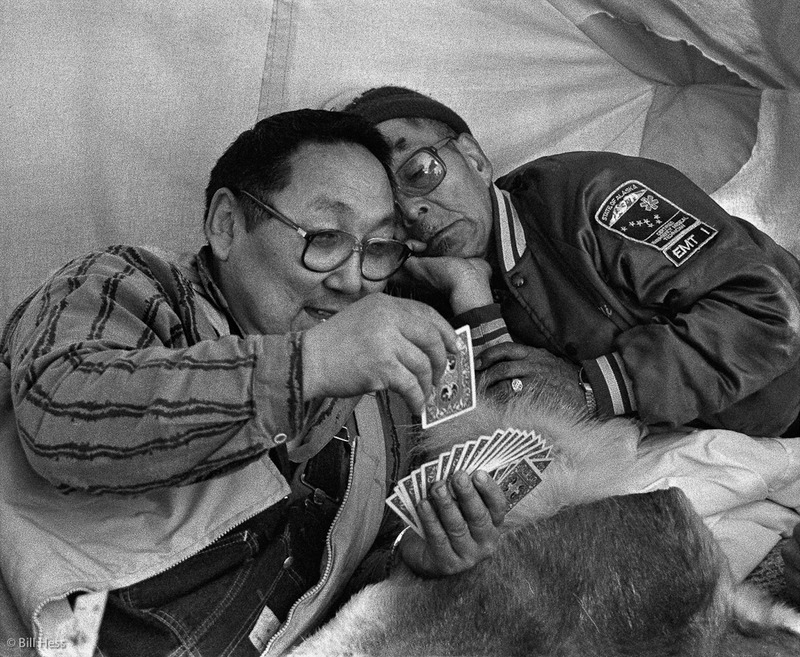

Before landing, we flew out over the hole for the aerial view.

Whale in the hole.

We landed on the shore. The slush had turned solid, but was still very thin. Helicopter pilot Price Brower, an Iñupiat whaler himself, tested the ice with his foot and determined that it was strong enough for us to walk on. So we headed toward the holes. but I was nervous. I judged the ice to be no more than three inches thick, if that. Salt water ice has an elasticity to it that freshwater ice does not, and I could feel the ice fall and rise beneath my boots as we walked toward the holes - somewhat the same effect that one might experience walking on a water bed - but not quite so pronounced.

I feared the action of the whales might cause the ice to crack and break beneath our feet.

Price seemed confident, so we all followed.

And then, right at the edge of the hole, helicopter pilot and Iñupiat whale hunter Price Brower dropped down onto his tummy. He inched his way toward the hole. Even as he did, the snout of the whale directly in front of him glided slowly through the water towards him.

Price reached out and touched the whale. The first physical contact between humanity and the stuck whales had been made. It would not be the last.

When we got back to Barrow, I learned Oran Caudle had done the very thing that I had hoped he would not - he had sent his footage to Channel 2 in Anchorage.

I knew that was it. The world's attention would now be riveted on Barrow, and on the whales. I felt that a natural tragedy was about to unfold, and the world would witness it, live on TV. I would not get to shoot my exclusive, solitary, tragic, essay, but would have to contend with the sharp elbows and hard shoves of the national news media - TV cameramen in particular.

I made prints of the final two images above and put them on the next jet to Anchorage, addrressed to the Anchorage Daily News. The Daily News ran the photo of Price and the whale looking at each other across the full width of its front page, with the one of the touch inset directly below it.

The photo editor asked me if they could put them on AP. I said go ahead. So off these pictures went, to appear in the newspapers of the world, both large and small.

Because of this, when I would later be talking with my peers in print media, they would blame me for setting off the whole insane, terrible, wonderful, absurd, cruel, compassionate, ruckus that followed.

But no, it wasn't my fault. I was not to blame. It was Oran Caudle's fault, for sending the video out, for sending moving images of our fellow, breathing, gasping, creatures, the whales, struggling against all odds for another breath, into practically every TV-equipped living room in the world.

I merely acted in self-defense, so as not to be totally innundated by the media onslaught that I knew would soon follow.

Even though I knew it would come, I didn't really know. How could anyone have known? The events that would soon take place would eclipse all preconception.

Now that I have started this gray whale series on my blog, I am committed and determined to finish it, but it is only now, as I prepare to post at 9:18 PM what I had anticipated posting between 3:00 and 4:00 PM that I have fully realized what a challenge I have given myself, what a time-consuming burden I have undertaken.

I am not an organized person. While the bulk of my gray whale rescue contact sheets negatives are all together, several are spread about elsewhere. I have not even located them all yet. I have no scanner with which to digitize them. Unless I had already scanned the images for my book, Gift of the Whale, the only means I have to digitize them is to photograph the negatives with one of my digital SLR cameras, then convert the negative images to a positives in Photoshop and then tweak that fairly low-grade (but still better, I think, than those produced by the low-cast scanners on the market) into a blog presentable image.

The process is more complicated and takes much longer than I had anticipated. Before I continue on, I need to regroup a bit, figure some things out, come up with better, swifter, methodology. I need to spend some real time figuring out not only what is in my contact sheets, but I must locate the negatives that are missing. I am confident that they are within six feet of where I now sit, but that doesn't mean they will be at all easy to find.

Tomorrow is Super Bowl Sunday. I figure that at least the US, if not the world, will be absorbed by the game. I think I will watch it, too. My family, or much of my family (Melanie is traveling in Southwest Alaska, Rex with Cortney in Hawaii and Caleb will probably join his buddies - I don't know what Lisa will do) will be here. So a great deal of my time is going to go, right there - to Super Bowl Sunday. I hope to eat more pizza than is good for me.

Other than this, I plan to spend the rest of my time exploring, figuring out what I have, trying to improve my camera "scanning" method and flow.

Maybe I will post something tomorrow, maybe not. By Monday, I hope to come back strong in the continuation of this series and then keep blasting away at it until it is done. It won't be early Monday, though. Early Monday, I must drive Marge back to Anchorage, so she can resume her babysitting duties.

p>

Complete series index:

Part 2: Roy finds the whales; Malik

Part 5: To rescue or euthanize

Part 6: Governor Cowper, ice punch, chainsaw holes

Part 7: Malik provides caribou for dinner

Part 8: CNN learns home is sacred place

Part 9: World's largest jet; Screw Tractor

Part 11: Portrait: Billy Adams and Malik

Part 12: Onboard Soviet icebreakers